The Bill That Could Kill Free Speech in Canada

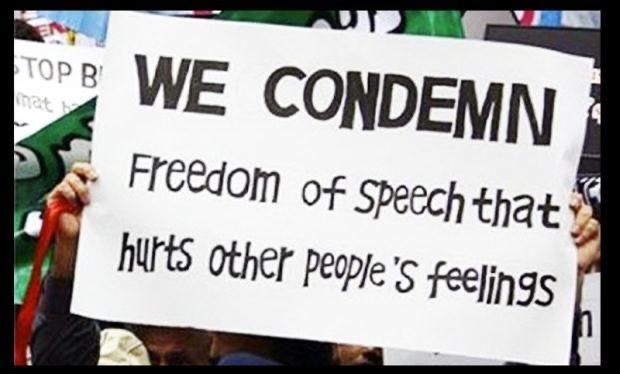

In February, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party introduced a bill aiming to protect children from online sexploitation. As noble as that is, the problem is that the legislation — Bill C-63 — also includes amendments that would effectively destroy free speech in Canada.

That’s because, in addition to amending the civil code regarding child pornography and sexual victimization, it makes several key changes to Canadian law regarding hate speech. Civil rights groups are sounding the alarm because it looks like the bill could be a Trojan horse used to silence political or cultural dissent.

Four Major Elements

The “Online Harms Act” has four parts. The first is the act itself, which sets up a “Digital Safety Commission” to deal with sexual violence and hold social media platforms accountable for any crimes in which they play a part. Part 4 focuses on the mandatory reporting of online child pornography.

Nobody seems to be protesting these parts of the bill. What people do have problems with are parts 2 and 3: amendments to the Criminal Code and Canadian Human Rights Act. These amendments have an Orwellian flavor that could penalize almost anyone with countercultural or biblical views that could be considered hateful — as the powers that be define it.

These amendments have an Orwellian flavor that could penalize almost anyone with countercultural or biblical views that could be considered hateful — as the powers that be define it.

Part 2 aims to formally define hate as “the emotion that involves detestation or vilification and that is stronger than disdain or dislike.” It adds that hate speech doesn’t apply to what merely offends or humiliates — and therefore, say critics, it could apply to anything unpopular.

The second major change would be to broaden the scope and punishment of hate crimes in Canada. Currently, the threshold for a “hate crime” is high, revolving around publicly promoting or inciting hatred. But if C-63 passes, it would be able to turn any existing offense into a hate crime carrying a longer sentence — including up to life in prison — by adding a separate offense to existing crimes if hate is a suspected motivation.

The consequences of this kind of addition could be surreal. As University of Saskatchewan law professor Dwight Newman says, “Let’s get real. Consider that a wayward 19-year-old painting graffiti who could be accused of being motivated by hatred could now be charged with an offence carrying the possibility of life imprisonment … a threat of life imprisonment is totally disproportionate to the offence.”

Online ‘Hate’ Speech

The third part of the bill would amend the Human Rights Act by adding “the communication of hate speech online” as a discriminatory practice. This means that individuals could complain to the Human Rights Commission when others say things about them online that they deem “hateful,” which could lead to fines of up to $50,000 and various restrictions against the offending party. In what some have called the most draconian provision of C-63, people could even be given peace bonds or put under house arrest if authorities believed they might commit hate speech in the future — a kind of pre-crime based only on suspicion. (Does the movie Minority Report come to mind here?) Even worse: complainants could remain anonymous and even receive up to $20,000 CAN in financial compensation if their accusation seems valid. This goes for hate crimes that exist in the real world or the supposed future.

Critics say this kind of legislation would not only incentivize people to make the complaints, but there would be so many that it would create an administrative backlog in the process. Frivolous complaints are supposed to be filtered out at the Commission stage but even then, defendants may have to shell out thousands of dollars to defend themselves. Only if the complaints make it past the Human Rights Commission and fail in the Human Rights Tribunal would a defendant be eligible to have their legal costs repaid.

What’s Clear

These are the nuts and bolts of C-63, but by now several things should be very apparent:

- The definition of “hate” is almost entirely subjective. There are no real-world metrics to distinguish hate speech from offensive speech.

- The process by which the legislation would be enforced makes it almost certain that abuses will occur. Canadian literary icon Margaret Atwood tweeted that C-63 would pave the way for false and vengeful accusations to be made, comparing it to the Lettres De Cachet — a reference to the ancien regime that existed in France until its Revolution. Under that, the king could sentence anyone to jail for anything merely by writing a letter against them.

- The way this bill has been proposed is curious, to say the least. If the Canadian government truly cared about protecting minors from online sexploitation, why would they include something as controversial as parts 2 and 3 in the legislation? A joint letter, signed by more than 20 civil rights groups and legal experts including Amnesty International Canada and the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, proposes moving parts 2 and 3 into a separate bill which would then be debated on its own. The letter states,

Bill C-63 enables blatant violations of expressive freedom, privacy, protest rights, and liberty. It also undermines the fundamental principles of democratic accountability and procedural fairness by granting sweeping powers to the new Digital Safety Commission.

The bill is still in the early stages of debate; the House of Commons has adjourned for the summer, so discussions won’t take place until mid-September. It does have support from the NDP party that formed a coalition with Trudeau to keep him in power.

But Pierre Poilievre, the leader of the official opposition, has called C-63 “an attack on freedom of expression.” Critics are encouraging everyone to write to their elected officials to air their concerns.

If the bill is eventually signed into law, Canada may serve as an unfortunate case study for the rest of the Western world. Similar laws already exist in some places in Europe, but none have such far-reaching implications. In the meantime, it’s important for Canadians to know what’s at stake and be diligent in defending the freedoms we currently enjoy — so that later generations, and the rest of the West, can enjoy them, too.